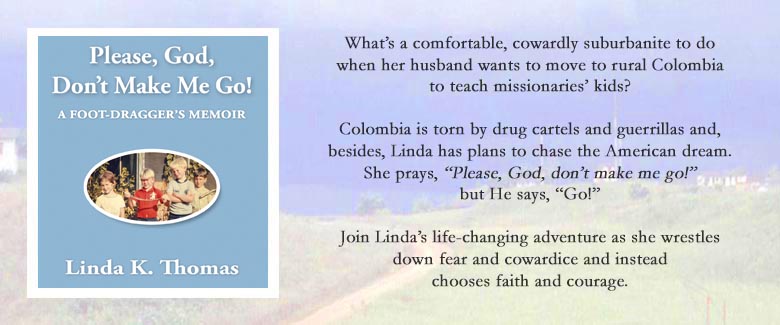

Within the

first two hours in our new home, Lomalinda, we’d experienced several pleasant

surprises, including warm welcomes from people who met us at the hangar when

the twin-engine plane, the Evangel, landed. (Click on Life at Lomalinda had gotten off to a great start!)

After

briefly showing us the house we’d live in—which far exceeded what I’d expected—dear David Hockett had driven us to the hub

of Lomalinda, on top of the outpost’s tallest hill, and showed us into the

dining hall, introducing us to several families eating their lunch at long

tables covered with white grease cloth. They, too, were enthusiastic with their

welcomes.

The

staff had expected us, thanks to someone’s foresight, so we found places set

for us. Lunch included spaghetti (we’d tasted better), fruit, plain white bread

with margarine, and a sugary drink. We were thankful for it—we were hungry.

Afterward,

we set out walking down a dirt track toward our house, the same steep winding

hill David Hockett had driven us up. Hiking without hats or umbrellas under

equatorial sun at midday was a shock to our Seattle sensibilities.

We

labored on, around curves, up little hills, down others, around more curves, across

a softball field, up a slight incline, and into the house that I was eager to

make into our home.

That

afternoon Dave headed to the school—more than eager to start the new year—while

I unpacked suitcases, footlocker, duffle bag, and boxes.

But

that wasn’t a straightforward task. The government, influenced by Marxist anti-American

sentiment, balked at issuing regular visas to new personnel, so our family had received

only tourist visas.

That

meant we couldn’t ship anything separately—we had to bring everything on the

plane in our baggage. Since every fraction of an inch mattered, we packed in a

way that would make the most items fit, not necessarily in an organized manner.

We

had wrapped breakables in clothes and towels, tucked silverware into shoes, and

hid valuables in lacy underwear—items we didn’t want to go missing during

customs and immigration like shortwave radio, cassette player, and jewelry.

As

a result, unpacking wasn’t efficient. I had to travel around the house

depositing items in the right places.

While I

unpacked, my sweet four-year-old Karen set up her bedroom, arranging stuffed

animals and play dishes in a little cupboard the previous occupants had left.

Here’s a photo of my gentle Karen Anne.

Seeing that

photo reminds me:

In those

days, all flights to Colombia left from Miami so, while still in the US,

that was our ultimate destination. Driving through the Midwest and Texas and

the South, we experienced heat like never before—being from Seattle, we didn’t

know what intense heat was!

So, to

help Karen keep cooler, we decided to have her beautiful long hair cut. The

woman at the Florida beauty shop must have been inexperienced because as I

watched, she was making a total mess.

I noticed

another beautician in the shop also watching nervously. Eventually she could

stand it no longer and took over the job herself. By then she could do almost

nothing to salvage Karen’s hair—I mean, how do you reattach hair that’s been cut

off?? The second lady did her best but poor Karen looked like a boy with a

shaggy cut that needed trimming.

When we

arrived in Lomalinda, people thought she was a boy. Poor dear girl. But she had

a good attitude, and it grew out eventually, and once again she, and we, enjoyed

her beautiful hair.

Progress: Sometimes we have to measure it in tiny segments.

In Lomalinda, due to the heat,

we had to move slower than we were accustomed to,

yet I was pleased and optimistic that on that first afternoon,

I was making good progress toward settling into our new home.

But I couldn't see into the future.

Things were about to change.