The

next morning, our first morning in Lomalinda, we awoke to a swishing, whooshing

noise outside. Dave got out of bed to investigate.

I

sat up, my heart singing because of the sun beaming through the windows—a

luxury for Seattle natives.

I

peeked through the curtains. Bent low to the ground, a local Colombian swung a

machete, shearing grasses in our yard.

Dave

knew only enough Spanish to say buenos días (hello), but

he stepped outside and struck up a conversation. Manuel had a ready smile, bright

white teeth, bronzed skin, and hair as black as the Colombian midnight sky.

A

flock of birds flew overhead—raucous, squawking green parrots. We soon learned

those calls would greet us every morning and again at the end of each day.

My

precious little kids tiptoed out of their bedrooms rubbing their eyes, looking

around the house, looking at me, looking at each other, looking as if they felt

like I so often did—Where am I? . . . Oh, now I remember. . . Lomalinda.

Outside,

Manuel continued to stoop over and swing his machete. His back must have ached something

awful.

Minutes

later the vast eastern sky loomed gray and soon turned pewter. It was as if we

were living Isaiah 41:22, “God sits enthroned above the circle of the earth. .

. . He stretches out the heavens like a canopy, and spreads them out. . . .”

Soon,

sharp wind gusts forced shrubs and palms and bamboo to bow westward. The

heavens grew black, and a blast of wind whipped the curtains off our living

room windows.

Dave

invited Manuel into our screened-in porch and, while they watched the

turbulence approach, Manuel taught him that rain is lluvia, and the big storm a

chubasco.

Then

it hit. Rain pounded our roof, hard and fast, and we had to shout if we wanted

to hear each other.

Rivers

gushed off our roof and, even though our house had wide eaves, rain blew inside

through the glass window slats. We could only gape in disbelief—we’d never seen

downpours like that in Seattle.

In

half an hour the storm had blown beyond us, leaving thick layers of mud in our

yard, our drive, our road—everywhere, everywhere—and for the rest of the day,

our shoes brought it into the house, orange and sticky.

It

had never occurred to me that in Lomalinda

we’d

have to live without pavement.

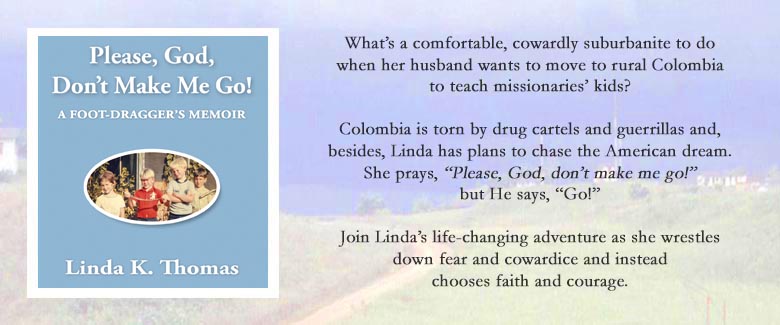

(from

Chapter 7,